Your Bible translation

- Thread starter Don1980

- Start date

-

Christian Chat is a moderated online Christian community allowing Christians around the world to fellowship with each other in real time chat via webcam, voice, and text, with the Christian Chat app. You can also start or participate in a Bible-based discussion here in the Christian Chat Forums, where members can also share with each other their own videos, pictures, or favorite Christian music.

If you are a Christian and need encouragement and fellowship, we're here for you! If you are not a Christian but interested in knowing more about Jesus our Lord, you're also welcome! Want to know what the Bible says, and how you can apply it to your life? Join us!

To make new Christian friends now around the world, click here to join Christian Chat.

did it originate with Luther? we'd need to look at the Germanic Bibles that predate it. which i will have a stab at.

it has 'ostern'

so no, this interpretive change in the text of the scripture did not originate with Luther.

-

1

- Show all

No longer Passover blood from OT sacrifices, but Passover because of the blood of Christ. The English word Easter describes the difference.

the text says pascha.

the translators decided to put something else; a word derived from the name of a pagan goddess.

the picture i'm getting from this preliminary research is that it probably stems from a disagreement between the roman bishopric & Asiatic churches in the first few centuries AD over whether Christians ought to be marking the anniversary of the Lord's sacrifice according to the Jewish, lunar calendar which Christ Himself followed, or whether they ought to be always using a sunday to observe the day in remembrance ((see: "quartodeciman controversy")). Christians in Asia Minor & Judea were keeping the Lord's Supper on 14 Nissan, but some in Rome insisted it should be on a sunday, and the controversy was so great that those in Rome excommunicated practically all of the churches in the East over it. the council in 325 thought to settle the matter by fiat, declaring that resurrection should be celebrated according to a calendar derived from the vernal equinox ((which happened to match the pagan celebration of spring goddess Astarte/Eostare/Ishtar by some weird 'coincidence')) rather than the way the scripture itself marks out the day of Pascha, per lunar cycle. 'since the council said so' meant that anyone who marked the day according to God's calendar per Leviticus would be excommunicated, which in that day was understood to mean, you go to hell if you don't do what we say. switch to calling it Eostare and celebrate it on a different day or be damned.

it would not surprise me to find in the end that the deliberate mistranslation of Pascha in Acts 12 and sometimes also in 1 Corinthians 5 was a politically motivated choice meant to erase the connection between the Lord's sacrifice and the 7 feast days of the Torah.

which, to me, is diabolically misguided.

JMO

-

3

- Show all

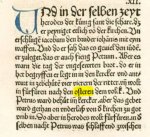

this is a screenshot from the Mentelin Bible of 1466, the first German-language Bible printed.

like the other pre-reformation Germanic Bibles i've been able to parse so far, it uses "ostern" i.e. Eostare instead of passha i.e. Pascha

here in Acts 12.

it definitely did not start with Luther but seems common in Germany -- however not so much in France, as i showed from the 13th century text i found.

obvious question that comes up for me is, what were the political/ideological relationships between Rome, where the observance of the resurrection was declared to be henceforth linked to Astarte's festival, with France vs. with Germany?

i ask because, the original Greek and the Latin transcriptions of it are without doubt using the word for Passover, and without doubt in the narrative of the scripture Christ's sacrifice is linked to Passover, the days of Unleavened Bread, and Firstfruits. in the first few centuries, the link between Christianity and Judaism was attempted to be erased, and Germanic translations of the Bible seem to follow course with this way of thinking and purposefully mis-translate Pascha. the French however did not do this, even though both were working from the same source texts, i.e. Jerome's Vulgate.

centuries later, when the Bible was being translated into English, there are also apparently two camps -- Tyndale puts Eostare, but Geneva puts Pascha. the KJV translating body, almost 100 years after the first English translations appeared, fell into the former camp -- which incidentally the official Catholic Bibles ((the Bishop's Bible)) also did. what was the stance of the church of England on removing the Jewishness of the Bible?

like the other pre-reformation Germanic Bibles i've been able to parse so far, it uses "ostern" i.e. Eostare instead of passha i.e. Pascha

here in Acts 12.

it definitely did not start with Luther but seems common in Germany -- however not so much in France, as i showed from the 13th century text i found.

obvious question that comes up for me is, what were the political/ideological relationships between Rome, where the observance of the resurrection was declared to be henceforth linked to Astarte's festival, with France vs. with Germany?

i ask because, the original Greek and the Latin transcriptions of it are without doubt using the word for Passover, and without doubt in the narrative of the scripture Christ's sacrifice is linked to Passover, the days of Unleavened Bread, and Firstfruits. in the first few centuries, the link between Christianity and Judaism was attempted to be erased, and Germanic translations of the Bible seem to follow course with this way of thinking and purposefully mis-translate Pascha. the French however did not do this, even though both were working from the same source texts, i.e. Jerome's Vulgate.

centuries later, when the Bible was being translated into English, there are also apparently two camps -- Tyndale puts Eostare, but Geneva puts Pascha. the KJV translating body, almost 100 years after the first English translations appeared, fell into the former camp -- which incidentally the official Catholic Bibles ((the Bishop's Bible)) also did. what was the stance of the church of England on removing the Jewishness of the Bible?

This passage is the very reason the word for Easter, for the Passover is changed from OT to NT. Christ is our Passover.

Does anyone have a translation that keeps best to the Hebrew?

The OT Passover is about Christ, it is an illustration of Christ and what Christ means to us. God is eternal and does not change. As soon as sin entered our world with Adam and the tree of knowledge, God set up a plan for our salvation to live with Him always, and that plan we are told demands blood of Christ. At first it was symbolic blood of Christ with the sacrificial system. We are told Christ fulfilled all that and made it perfect. Scripture should not add to or take away from God's eternal plan.

Does anyone have a translation that keeps best to the Hebrew?

Does anyone have a translation that keeps best to the Hebrew?

Modern bibles proclaim the "OLD pascha" in a post-resurrection context in Acts 12:4.

The Authorised Version proclaims the "NEW pascha" in a post-resurrection context in Acts 12:4. Yea, the Authorised Version proclaims the RESURRECTION OF JESUS CHRIST.

"Let no man therefore judge you in meat, or in drink, or in respect of an holyday, or of the new moon, or of the sabbath days: Which are a shadow of things to come; but the body is of Christ." Colossians 2:16-17

The Authorised Version proclaims the "NEW pascha" in a post-resurrection context in Acts 12:4. Yea, the Authorised Version proclaims the RESURRECTION OF JESUS CHRIST.

"Let no man therefore judge you in meat, or in drink, or in respect of an holyday, or of the new moon, or of the sabbath days: Which are a shadow of things to come; but the body is of Christ." Colossians 2:16-17

-

1

- Show all

William Tyndale INVENTED the English word PASSOVER. As the Trinitarian Bible Society noted --

"When he [Tyndale] began his translation of the Pentateuch, he was again faced with the problem in Exodus 12:11 and twenty-one other places, and no doubt recognizing that Easter in this context would be an anachronism he coined a new word, PASSOVER, and used it consistently in all twenty-two places. It is, therefore, to Tyndale that our language is indebted for this meaningful and appropriate word."

William Tyndale did not use his own word in Acts 12:4. William Tyndale employed the word ESTER in his translation of Acts 12:4. He invented the other word - PASSOVER - yet, he determined that his own word did not accurately represent the Greek word PASCHA in Acts 12:4. That's because William Tyndale, like the Apostles before him and the Authorised Version translators after him, was also jealous for the RESURRECTION OF JESUS CHRIST.

Let's state the matter in plain English - the man who coined the word Passover for the English language affirmed that Passover was not the correct rendering of pascha in Acts 12:4. In fact, in his 1534 version, Tyndale did not use his own word even once in the New Testament. Rather, Tyndale varied his definitions of pascha frequently in the New Testament, sometimes referring to it as ester, sometimes paschall lambe, sometimes ester lambe, sometimes ester fest, and so forth, but never Passover, even though he invented the word Passover.

Moreover, William Tyndale was the first person to employ the word ester in an English Bible. Ester later morphed into Easter, as we saw earlier, thus dispelling the absurd notion that the term Easter had pagan origins. Prior to Tyndale, the Greek word pascha was simply transliterated. Again from the Trinitarian Bible Society --

In a nutshell, if the inventor of the word Passover did not apply it to pascha in Acts 12:4, it is nothing less than arrogant and presumptuous - not to mention utterly foolish - for newcomers to maintain that the inventor of the word got it wrong. The newcomers are too late, for the very word they are insisting upon - Passover - was minted by another, and he did not insist upon a rigid meaning, and since he invented it - alea iacta est.

Conversely, it is eminently refreshing to read the words of a man like John Burgon, a truly born-again Christian who was himself an absolute master of various languages, including Greek, Latin and English. And yet, not even Burgon could hold a candle to the translators of the Authorised Version, and Burgon understood that, for he greatly lamented the uncouth production of Westcott and Hort who, like the scholars of our day, demonstrated a complete and utter slavery to a language they barely even understood. It hasn't changed.

In Burgon's day, however, he literally rejoiced when describing the grace and brilliance of the translators of the Authorised Version. Commenting on the various semantic shades and varying contexts of seemingly static words, a concept which must be thoroughly understood before one even begins to translate God's Word, Burgon noted --

"The Translators' of 1611, towards the close of their long and quaint Address 'to the Reader,' offer the following statement concerning what had been their own practice - 'We have not tied ourselves' (say they) 'to an uniformity of phrasing, or to an identity of words, as some peradventure would wish that we had done.' On this, they presently enlarge. We have been 'especially careful,' have even 'made a conscience,' 'not to vary from the sense of that which we had translated before, if the word signified the same thing in both places.' But then, (as they shrewdly point out in passing,) 'there be some words that be not of the same sense everywhere.' And had this been the sum of their avowal, no one with a spark of Taste, or with the least appreciation of what constitutes real Scholarship, would have been found to differ from them." [10]

It is clear from that statement what Burgon would think of modern "scholarship." He continues --

"But then it speedily becomes evident that, at the bottom of all this, there existed in the minds of the Revisionists of 1611 a profound - shall we not rather say a prophetic? - consciousness, that the fate of the English Language was bound up with the fate of their Translation... Of all this, the great Scholars of 1611 showed themselves profoundly conscious... Verily, those men understood their craft! 'There were giants in those days.' As little would they submit to be bound by the new cords of the Philistines as by their green withes. Upon occasion, they could shake themselves free from either. And why? For the selfsame reason: viz. because the Spirit of their God was mightily upon them." [11]

The truly born-again believer can only say, "Amen and amen!"

Burgon's wise words must be allowed yet one more hearing. After exposing the abhorrent translation of Westcott & Hort, whose deplorable quality and tastelessness and inaccuracies have been reproduced ad nauseam in modern bibles without exception, Burgon made this observation --

"Our contention, so far, has been but this - that it does not by any means follow that identical Greek words and expressions, wherever occurring, are to be rendered by identical words and expressions in English... The truth is - as all who have given real thought to the subject must be aware - the phenomena of Language are among the most subtle and delicate imaginable: the problem of Translation, one of the most many-sided and difficult that can be named. And if this holds universally, in how much greater a degree when the book to be translated is the Bible! Here, anything like a mechanical leveling up of terms, every attempt to impose a pre-arranged system of uniform rendering on words - every one of which has a history and (so to speak) a will of its own - is inevitably destined to result in discomfiture and disappointment. But what makes this so very serious a matter is that, because holy scripture is the Book experimented upon, the loftiest interests that can be named become imperiled; and it will constantly happen that what is not perhaps in itself a very serious mistake, may yet inflict irreparable injury." [12]

And then speaking of the mastery of the Authorised Version, Burgon discloses --

"There are, after all, mightier laws in the Universe than those of grammar. In the quaint language of our Translators of 1611: 'For is the Kingdom of God become words or syllables? Why should we be in bondage to them if we may be free?'" [13]

"When he [Tyndale] began his translation of the Pentateuch, he was again faced with the problem in Exodus 12:11 and twenty-one other places, and no doubt recognizing that Easter in this context would be an anachronism he coined a new word, PASSOVER, and used it consistently in all twenty-two places. It is, therefore, to Tyndale that our language is indebted for this meaningful and appropriate word."

William Tyndale did not use his own word in Acts 12:4. William Tyndale employed the word ESTER in his translation of Acts 12:4. He invented the other word - PASSOVER - yet, he determined that his own word did not accurately represent the Greek word PASCHA in Acts 12:4. That's because William Tyndale, like the Apostles before him and the Authorised Version translators after him, was also jealous for the RESURRECTION OF JESUS CHRIST.

Let's state the matter in plain English - the man who coined the word Passover for the English language affirmed that Passover was not the correct rendering of pascha in Acts 12:4. In fact, in his 1534 version, Tyndale did not use his own word even once in the New Testament. Rather, Tyndale varied his definitions of pascha frequently in the New Testament, sometimes referring to it as ester, sometimes paschall lambe, sometimes ester lambe, sometimes ester fest, and so forth, but never Passover, even though he invented the word Passover.

Moreover, William Tyndale was the first person to employ the word ester in an English Bible. Ester later morphed into Easter, as we saw earlier, thus dispelling the absurd notion that the term Easter had pagan origins. Prior to Tyndale, the Greek word pascha was simply transliterated. Again from the Trinitarian Bible Society --

In a nutshell, if the inventor of the word Passover did not apply it to pascha in Acts 12:4, it is nothing less than arrogant and presumptuous - not to mention utterly foolish - for newcomers to maintain that the inventor of the word got it wrong. The newcomers are too late, for the very word they are insisting upon - Passover - was minted by another, and he did not insist upon a rigid meaning, and since he invented it - alea iacta est.

Conversely, it is eminently refreshing to read the words of a man like John Burgon, a truly born-again Christian who was himself an absolute master of various languages, including Greek, Latin and English. And yet, not even Burgon could hold a candle to the translators of the Authorised Version, and Burgon understood that, for he greatly lamented the uncouth production of Westcott and Hort who, like the scholars of our day, demonstrated a complete and utter slavery to a language they barely even understood. It hasn't changed.

In Burgon's day, however, he literally rejoiced when describing the grace and brilliance of the translators of the Authorised Version. Commenting on the various semantic shades and varying contexts of seemingly static words, a concept which must be thoroughly understood before one even begins to translate God's Word, Burgon noted --

"The Translators' of 1611, towards the close of their long and quaint Address 'to the Reader,' offer the following statement concerning what had been their own practice - 'We have not tied ourselves' (say they) 'to an uniformity of phrasing, or to an identity of words, as some peradventure would wish that we had done.' On this, they presently enlarge. We have been 'especially careful,' have even 'made a conscience,' 'not to vary from the sense of that which we had translated before, if the word signified the same thing in both places.' But then, (as they shrewdly point out in passing,) 'there be some words that be not of the same sense everywhere.' And had this been the sum of their avowal, no one with a spark of Taste, or with the least appreciation of what constitutes real Scholarship, would have been found to differ from them." [10]

It is clear from that statement what Burgon would think of modern "scholarship." He continues --

"But then it speedily becomes evident that, at the bottom of all this, there existed in the minds of the Revisionists of 1611 a profound - shall we not rather say a prophetic? - consciousness, that the fate of the English Language was bound up with the fate of their Translation... Of all this, the great Scholars of 1611 showed themselves profoundly conscious... Verily, those men understood their craft! 'There were giants in those days.' As little would they submit to be bound by the new cords of the Philistines as by their green withes. Upon occasion, they could shake themselves free from either. And why? For the selfsame reason: viz. because the Spirit of their God was mightily upon them." [11]

The truly born-again believer can only say, "Amen and amen!"

Burgon's wise words must be allowed yet one more hearing. After exposing the abhorrent translation of Westcott & Hort, whose deplorable quality and tastelessness and inaccuracies have been reproduced ad nauseam in modern bibles without exception, Burgon made this observation --

"Our contention, so far, has been but this - that it does not by any means follow that identical Greek words and expressions, wherever occurring, are to be rendered by identical words and expressions in English... The truth is - as all who have given real thought to the subject must be aware - the phenomena of Language are among the most subtle and delicate imaginable: the problem of Translation, one of the most many-sided and difficult that can be named. And if this holds universally, in how much greater a degree when the book to be translated is the Bible! Here, anything like a mechanical leveling up of terms, every attempt to impose a pre-arranged system of uniform rendering on words - every one of which has a history and (so to speak) a will of its own - is inevitably destined to result in discomfiture and disappointment. But what makes this so very serious a matter is that, because holy scripture is the Book experimented upon, the loftiest interests that can be named become imperiled; and it will constantly happen that what is not perhaps in itself a very serious mistake, may yet inflict irreparable injury." [12]

And then speaking of the mastery of the Authorised Version, Burgon discloses --

"There are, after all, mightier laws in the Universe than those of grammar. In the quaint language of our Translators of 1611: 'For is the Kingdom of God become words or syllables? Why should we be in bondage to them if we may be free?'" [13]

Better toss your KJV then, given that it was built from Greek texts translated by a Catholic. No end of corruption there!

Regarding the origins of the Reformation, it has been said by Catholic enemies thereof that "Erasmus laid the eggs and Luther hatched the chickens." Other Catholic enemies of both Erasmus and Luther charged that "Erasmus is the father of Luther." [2] These charges were based upon the fact that Luther was influenced in no small measure by Erasmus's publication of his Greek New Testament in 1516. In that year, there was no Reformation nor were there yet any official Protestants.

William Tyndale INVENTED the English word PASSOVER. As the Trinitarian Bible Society noted --

"When he [Tyndale] began his translation of the Pentateuch, he was again faced with the problem in Exodus 12:11 and twenty-one other places, and no doubt recognizing that Easter in this context would be an anachronism he coined a new word, PASSOVER, and used it consistently in all twenty-two places. It is, therefore, to Tyndale that our language is indebted for this meaningful and appropriate word."

"When he [Tyndale] began his translation of the Pentateuch, he was again faced with the problem in Exodus 12:11 and twenty-one other places, and no doubt recognizing that Easter in this context would be an anachronism he coined a new word, PASSOVER, and used it consistently in all twenty-two places. It is, therefore, to Tyndale that our language is indebted for this meaningful and appropriate word."

the word pascha is a Greek transliteration of the Hebrew pacach and it literally means "to pass over"For the LORD will pass through to smite the Egyptians; and when He seeth the blood upon the lintel, and on the two side posts, the LORD will pass over the door, and will not suffer the destroyer to come in unto your houses to smite you.

(Exodus 12:23)

Strong's Concordance

pacach: halt

Original Word: פָסַח

Part of Speech: Verb

Transliteration: pacach

Phonetic Spelling: (paw-sakh')

Definition: to pass or spring over

all he did was translate it literally -- including in 1 Corinthians 5:7, btw -- except for in one instance, in Acts 12:4, where he purposefully mistranslated the word and used an appropriated transliteration of the name of a pagan Greek festival celebrating Eostare their dawn/spring goddess, which is a derivative of the ancient goddess Astarte / Ashereh -- in keeping with the papal decree. "facts"

-

1

- Show all

the word pascha is a Greek transliteration of the Hebrew pacach and it literally means "to pass over"For the LORD will pass through to smite the Egyptians; and when He seeth the blood upon the lintel, and on the two side posts, the LORD will pass over the door, and will not suffer the destroyer to come in unto your houses to smite you.

(Exodus 12:23)

Strong's Concordance

pacach: halt

Original Word: פָסַח

Part of Speech: Verb

Transliteration: pacach

Phonetic Spelling: (paw-sakh')

Definition: to pass or spring over

all he did was translate it literally -- including in 1 Corinthians 5:7, btw -- except for in one instance, in Acts 12:4, where he purposefully mistranslated the word and used an appropriated transliteration of the name of a pagan Greek festival celebrating Eostare their dawn/spring goddess, which is a derivative of the ancient goddess Astarte / Ashereh -- in keeping with the papal decree. "facts"

Purposely correctly translated to proclaim the resurrection of Christ. BTW, the catholic Bible says passover, not easter.

-

2

-

1

- Show all

This is a misrepresentation of the facts, and overlooks important historical context.

First, while it's true that the majority of extant manuscripts fall into the Byzantine family, but it isn't "almost all available witnesses". Second, "majority rules" is not relevant when it comes to determining truth. Third, the violent spread of Islam in the seventh century resulted in the destruction of many manuscripts. Fourth, you're arguing in circles, assuming that "Sin-Vat" is corrupt.

First, while it's true that the majority of extant manuscripts fall into the Byzantine family, but it isn't "almost all available witnesses". Second, "majority rules" is not relevant when it comes to determining truth. Third, the violent spread of Islam in the seventh century resulted in the destruction of many manuscripts. Fourth, you're arguing in circles, assuming that "Sin-Vat" is corrupt.

“If we will be sons of the truth, we must...trample upon our own credit...”

“[W]e have at the length, through the good hand of the Lord upon us, brought the work to that pass that you now see” (The Translators).

The king’s translators believe what’s in the bible in “comparing spiritual things with spiritual.” Here’s the difference, you believe man is the final authority – this is “…which man’s wisdom teacheth” but the KJ translators believe the “which the Holy Ghost teacheth”. You have put man’s reasoning above the scripture, No you cannot do that with God who is infinite. God is not a respecter of person whether you sound logically or not, whether one is scholar or not when God’s word is undermined, we know there is no respect of that person.

1Co 2:13 Which things also we speak, not in the words which man's wisdom teacheth, but which the Holy Ghost teacheth; comparing spiritual things with spiritual.

Isa_1:18 Come now, and let us reason together, saith the LORD: though your sins be as scarlet, they shall be as white as snow; though they be red like crimson, they shall be as wool.

Act_10:34 Then Peter opened his mouth, and said, Of a truth I perceive that God is no respecter of persons:

Now to explain further the view of a Textual critic for putting man over God’s word as the final written authority is indeed a very dangerous for one results to what we call “conjectural emendations” meaning the textual critic is doing an educated guess. Reading the Encyclopedia Americana Vol. III p. 656 has this to say about the textual critic and I quote:

“But after all this involved work of identification, classification and reconstruction by hypothesis has been finished, the textual critic’s labors are not ended. In many cases, he must still decide…and in some cases he may have to resort to conjectural emendations…”

Your choice, Holy Ghost teaches or mere man’s reasoning or wisdom. My choice- What the holy Ghost teaches. Scripture my final written authority.

-

1

- Show all

No longer Passover blood from OT sacrifices, but Passover because of the blood of Christ. The English word Easter describes the difference.

-

3

- Show all

Dino dear,

God is the preserver of life. If God can protect his children in the past, he too can protect and preserve his words. And what does the unholy hand of Muslims have to do with the Holy words of God? Do you think God is not capable to preserve his words? You joking me Dino. “Lest Satan should get an advantage of us: for we are not ignorant of his devices.” (2 Corinthians 2:11). God is still in control even though Muslim world spread over in the European Continent. The invocation of Muslim has nothing to do with the English bible. Btw, granting Muslims did a terrible things in the past then it is must be affirmed that even today with the vast technology has still no “wealth of information” since the “wealth of information” were vanished during the 17th Ce. Yet this is not true. You fake information about the English bibles.

What I said was about a fact, that the KJV generally holds the greater witnesses than the newer versions, since I cannot be charged with circular reasoning. It must be you that circles around with your false logical thinking about the KJV and perhaps a wrong information about the witnesses that I am talking about. You just mention one witness after all but I am talking of the 3 witnesses. A three-fold cord is not easily broken. These three witnesses I am referring to are:

God is the preserver of life. If God can protect his children in the past, he too can protect and preserve his words. And what does the unholy hand of Muslims have to do with the Holy words of God? Do you think God is not capable to preserve his words? You joking me Dino. “Lest Satan should get an advantage of us: for we are not ignorant of his devices.” (2 Corinthians 2:11). God is still in control even though Muslim world spread over in the European Continent. The invocation of Muslim has nothing to do with the English bible. Btw, granting Muslims did a terrible things in the past then it is must be affirmed that even today with the vast technology has still no “wealth of information” since the “wealth of information” were vanished during the 17th Ce. Yet this is not true. You fake information about the English bibles.

What I said was about a fact, that the KJV generally holds the greater witnesses than the newer versions, since I cannot be charged with circular reasoning. It must be you that circles around with your false logical thinking about the KJV and perhaps a wrong information about the witnesses that I am talking about. You just mention one witness after all but I am talking of the 3 witnesses. A three-fold cord is not easily broken. These three witnesses I am referring to are:

- The Copies. These are divided into 3 groups, the miniscules, the majuscule/uncials and the lectionaries. Of this copies witness generally favors the KJV which you concurred.

- The Versions. The Peshitta, the Old Latin, the Italic Version, the Gothic bible , Geneva French bible,etc. which favors the KJV more than the newer versions.

- The quotation from the Church Fathers which favors the Byzantine type in origin than the Alexandrian type especially in many of the disputed passages of the Bible.

-

2

- Show all

Further, witnesses as fa as the bible is concerned is counted. There is greater weight of judgment when there are more witnesses to a fact especially when they corroborate with each other than a few witnesses that are in contrast with each or that cannot understand one another.

-

1

- Show all

Purposely correctly translated to proclaim the resurrection of Christ. BTW, the catholic Bible says passover, not easter.

-

1

- Show all

Are you saying the Lord has never used symbolism to teach us? Do you think the Lord was just spinning his wheels as the Lord gave us Passover?

-

1

- Show all

I think I need to challenge once again your “contextual history” since this is not an understandable history of the English Bible speaking of the KJV. In the first place you have nothing to offer me by exposing your true color “that man is the final authority” relative to the scripture or the words of God, while I believe that the scriptures has the authority over man.

Once again you have misrepresented my words. That's a good way to get on my bad side.

What I wrote was in response to John146, who wrote, "If we don't have the pure words of God translated in the English language, then man's education is going to be the final authority on what God has said."

My words in response were, "Given that it was educated men who translated the Bible into English, "man's education" is the "final authority" no matter which translation you prefer."

So I did not write, "man is the final authority". The point I was making is that the Scripture was translated by men into English. The Holy Spirit inspired the original-language texts, not the English texts.

Scripture is also my final authority. However, I don't attribute any higher spirituality, intelligence, or inspiration to the translators of the KJV than I do for any other well-intentioned translation. Today we don't need conjectural emendations as were needed in 1611.

Once again you have misrepresented my words. That's a good way to get on my bad side.

What I wrote was in response to John146, who wrote, "If we don't have the pure words of God translated in the English language, then man's education is going to be the final authority on what God has said."

My words in response were, "Given that it was educated men who translated the Bible into English, "man's education" is the "final authority" no matter which translation you prefer."

So I did not write, "man is the final authority". The point I was making is that the Scripture was translated by men into English. The Holy Spirit inspired the original-language texts, not the English texts.

This is why I said the king’s men treated the scriptures as their written authority and that they are only a poor “instruments”. They further wrote,

“If we will be sons of the truth, we must...trample upon our own credit...”

“[W]e have at the length, through the good hand of the Lord upon us, brought the work to that pass that you now see” (The Translators).

The king’s translators believe what’s in the bible in “comparing spiritual things with spiritual.” Here’s the difference, you believe man is the final authority – this is “…which man’s wisdom teacheth” but the KJ translators believe the “which the Holy Ghost teacheth”. You have put man’s reasoning above the scripture, No you cannot do that with God who is infinite. God is not a respecter of person whether you sound logically or not, whether one is scholar or not when God’s word is undermined, we know there is no respect of that person.

1Co 2:13 Which things also we speak, not in the words which man's wisdom teacheth, but which the Holy Ghost teacheth; comparing spiritual things with spiritual.

Isa_1:18 Come now, and let us reason together, saith the LORD: though your sins be as scarlet, they shall be as white as snow; though they be red like crimson, they shall be as wool.

Act_10:34 Then Peter opened his mouth, and said, Of a truth I perceive that God is no respecter of persons:

Now to explain further the view of a Textual critic for putting man over God’s word as the final written authority is indeed a very dangerous for one results to what we call “conjectural emendations” meaning the textual critic is doing an educated guess. Reading the Encyclopedia Americana Vol. III p. 656 has this to say about the textual critic and I quote:

“But after all this involved work of identification, classification and reconstruction by hypothesis has been finished, the textual critic’s labors are not ended. In many cases, he must still decide…and in some cases he may have to resort to conjectural emendations…”

Your choice, Holy Ghost teaches or mere man’s reasoning or wisdom. My choice- What the holy Ghost teaches. Scripture my final written authority.

“If we will be sons of the truth, we must...trample upon our own credit...”

“[W]e have at the length, through the good hand of the Lord upon us, brought the work to that pass that you now see” (The Translators).

The king’s translators believe what’s in the bible in “comparing spiritual things with spiritual.” Here’s the difference, you believe man is the final authority – this is “…which man’s wisdom teacheth” but the KJ translators believe the “which the Holy Ghost teacheth”. You have put man’s reasoning above the scripture, No you cannot do that with God who is infinite. God is not a respecter of person whether you sound logically or not, whether one is scholar or not when God’s word is undermined, we know there is no respect of that person.

1Co 2:13 Which things also we speak, not in the words which man's wisdom teacheth, but which the Holy Ghost teacheth; comparing spiritual things with spiritual.

Isa_1:18 Come now, and let us reason together, saith the LORD: though your sins be as scarlet, they shall be as white as snow; though they be red like crimson, they shall be as wool.

Act_10:34 Then Peter opened his mouth, and said, Of a truth I perceive that God is no respecter of persons:

Now to explain further the view of a Textual critic for putting man over God’s word as the final written authority is indeed a very dangerous for one results to what we call “conjectural emendations” meaning the textual critic is doing an educated guess. Reading the Encyclopedia Americana Vol. III p. 656 has this to say about the textual critic and I quote:

“But after all this involved work of identification, classification and reconstruction by hypothesis has been finished, the textual critic’s labors are not ended. In many cases, he must still decide…and in some cases he may have to resort to conjectural emendations…”

Your choice, Holy Ghost teaches or mere man’s reasoning or wisdom. My choice- What the holy Ghost teaches. Scripture my final written authority.

-

1

- Show all

Dino dear,

God is the preserver of life. If God can protect his children in the past, he too can protect and preserve his words. And what does the unholy hand of Muslims have to do with the Holy words of God? Do you think God is not capable to preserve his words? You joking me Dino. “Lest Satan should get an advantage of us: for we are not ignorant of his devices.” (2 Corinthians 2:11). God is still in control even though Muslim world spread over in the European Continent. The invocation of Muslim has nothing to do with the English bible. Btw, granting Muslims did a terrible things in the past then it is must be affirmed that even today with the vast technology has still no “wealth of information” since the “wealth of information” were vanished during the 17th Ce. Yet this is not true. You fake information about the English bibles.

What I said was about a fact, that the KJV generally holds the greater witnesses than the newer versions, since I cannot be charged with circular reasoning. It must be you that circles around with your false logical thinking about the KJV and perhaps a wrong information about the witnesses that I am talking about. You just mention one witness after all but I am talking of the 3 witnesses. A three-fold cord is not easily broken. These three witnesses I am referring to are:

God is the preserver of life. If God can protect his children in the past, he too can protect and preserve his words. And what does the unholy hand of Muslims have to do with the Holy words of God? Do you think God is not capable to preserve his words? You joking me Dino. “Lest Satan should get an advantage of us: for we are not ignorant of his devices.” (2 Corinthians 2:11). God is still in control even though Muslim world spread over in the European Continent. The invocation of Muslim has nothing to do with the English bible. Btw, granting Muslims did a terrible things in the past then it is must be affirmed that even today with the vast technology has still no “wealth of information” since the “wealth of information” were vanished during the 17th Ce. Yet this is not true. You fake information about the English bibles.

What I said was about a fact, that the KJV generally holds the greater witnesses than the newer versions, since I cannot be charged with circular reasoning. It must be you that circles around with your false logical thinking about the KJV and perhaps a wrong information about the witnesses that I am talking about. You just mention one witness after all but I am talking of the 3 witnesses. A three-fold cord is not easily broken. These three witnesses I am referring to are:

- The Copies. These are divided into 3 groups, the miniscules, the majuscule/uncials and the lectionaries. Of this copies witness generally favors the KJV which you concurred.

- The Versions. The Peshitta, the Old Latin, the Italic Version, the Gothic bible , Geneva French bible,etc. which favors the KJV more than the newer versions.

- The quotation from the Church Fathers which favors the Byzantine type in origin than the Alexandrian type especially in many of the disputed passages of the Bible.

-

2

- Show all