Is Christmas paganism?

- Thread starter StandTro

- Start date

-

Christian Chat is a moderated online Christian community allowing Christians around the world to fellowship with each other in real time chat via webcam, voice, and text, with the Christian Chat app. You can also start or participate in a Bible-based discussion here in the Christian Chat Forums, where members can also share with each other their own videos, pictures, or favorite Christian music.

If you are a Christian and need encouragement and fellowship, we're here for you! If you are not a Christian but interested in knowing more about Jesus our Lord, you're also welcome! Want to know what the Bible says, and how you can apply it to your life? Join us!

To make new Christian friends now around the world, click here to join Christian Chat.

This thread isn't asking but is Christmas paganism. In its origins, yes, it is.

Freedom people? Wow. How far do you think to teach that is to go?

Freedom to what? Are there restrictions on what you think of as freedom in Christ?

Freedom people? Wow. How far do you think to teach that is to go?

Freedom to what? Are there restrictions on what you think of as freedom in Christ?

We are truly free to do all these things, but we will also give account to God. And His Son has already given the Judgment.

Matt. 7:

22 Many will say to me in that day, Lord, Lord, have we not prophesied in thy name? and in thy name have cast out devils? and in thy name done many wonderful works?

These all surely had Freedom my friend, to live and worship in whichever manner they desired. Even Giving the Christ credit for it all.

23 And then will I profess unto them, I never knew you: depart from me, ye that work iniquity.

But these used their "Freedom" to pursue a religion with religious traditions which acknowledged the Christ, but transgressed God's Laws. It didn't work out so well for them according to my Master.

We also have the "Freedom" to listen and "DO" as the Christ instructs. We also have the freedom NOT to add to His instructions or take away from them. We have the freedom to SERVE HIM over religious traditions of the land. This would of course be the unpopular choice as the Christ Himself showed us when He chose God's Ways over the religious traditions of man.

Shouldn't we use this "Freedom" to "prove" what is that acceptable Will of God?

Rom. 12:

1 I beseech you therefore, brethren, by the mercies of God, that ye present your bodies a living sacrifice, holy, acceptable unto God, which is your reasonable service.

Would this be a wise way to use our "Freedom"?

2 And be not conformed to this world:

Would this also include the religions and religious traditions of this World, would it not?

but be ye transformed by the renewing of your mind, that ye may prove what is that good, and acceptable, and perfect, will of God.

I think we should consider using the Freedom He gives us to Serve Him and His Ways over the religious traditions of the land.

We are surely free to do that as well..

well that's Jesus talking. so why are you still in the OT? we don't have to keep the law...if you keep reading in the NT, you will instruction on that very thing. read the verse you quoted...I think you missed it:

UNTIL John the law and the prophets were...SINCE that time, the Kingdom of God is preached...how do you enter the kingdom?

by believing in Christ and that He died for your sins and was resurrected and has ascended into heaven and sits at the right hand of God. He lives forevermore to make intercession for us. He is our High Priest and God has found His sacrifice perfect and it is the final one. yet you keep going back to the law

you are concerned with dead things. let the dead bury the dead then.

UNTIL John the law and the prophets were...SINCE that time, the Kingdom of God is preached...how do you enter the kingdom?

by believing in Christ and that He died for your sins and was resurrected and has ascended into heaven and sits at the right hand of God. He lives forevermore to make intercession for us. He is our High Priest and God has found His sacrifice perfect and it is the final one. yet you keep going back to the law

you are concerned with dead things. let the dead bury the dead then.

Luke 16:16-17, "The Law and the Prophets were until John, since that time the Kingdom of YHWH is preached, and every man is pressed to enter it. But it is easier for heaven and earth to pass, than one yodh of the Law to fail."

That means the Law is not gone, the Law and prophets were preached up until Yahshua came, as nothing has been added to them since, but He said the earth will pass before the Law does...

and your accusations about "still in the OT" is nonsense, I take the entire word, just posted a quote about live by the entire ward and your implying to ignore half of it...

Well this is the NT, does quoting this make me or make Yahshua/Jesus a bad bad pharisee legalisim layer, etc, etc, etc?

Revelation 22:11-15, “He who does wrong, let him do more wrong; he who is filthy, let him be more filthy; he who is righteous, let him be more righteous; he who is set-apart, let him be more set-apart. And see, I am coming speedily, and My reward is with Me, to give to each according to his work. “I am the ‘Aleph’ and the ‘Taw’, the Beginning and the End, the First and the Last. Blessed are those doing His commands, so that the authority shall be theirs unto the tree of life, and to enter through the gates into the city. But outside are the dogs and those who enchant with drugs, and those who whore, and the murderers, and the idolaters, and all who love and do falsehood.”

-

1

- Show all

You set up false dichotomy in what you say.

Everybody has what they believe is right, what is right lines up with the Scripture. In this case, Christmas, by every measurement is pagan in origins, implementation and practice. Now this is why I say you are posing a false dichotomy, if you can show me in the word where Christmas is then I will repent, if you can not it seems you have no Scripture to stand on but only tradition.

You are saying I/m wrong but according to the Messiah out doctrine should be based in the ENTIRE word:

Mat 4:4, “But He answering, said, “It has been written, ‘Man shall not live by bread alone, but by every word that comes from the mouth of יהוה.” (Deut 8:3)

and also He says to do and promote the Law:

Matthew 5:17-19, “Do not think that I came to destroy the Torah or the Prophets. I did not come to destroy but to fulfill. For truly, I say to you, till the heaven and the earth pass away, one yod or one tittle shall by no means pass from the Torah till all be done. Whoever, then, breaks one of the least of these commands, and teaches men so, shall be called least in the reign of the heavens; but whoever does and teaches them, he shall be called great in the reign of the heavens.”

Revelation 21:1, "I saw a new heaven and a new earth, for the first heaven and the first earth had passed away."

So the options are what? If I sin once I have to turn completely away from the Most High's Instructions? WIthout the Law there is no sin. Since we can sin the Law remains, just as Yahshua said. Do not steal, do not covet, have none before YHWH, etc. are good things.

1 John 1:8-10, "If we say that we have no sin, we deceive ourselves, and the truth is not in us. If we confess our sins, He is faithful and just to forgive us our sins, and to cleanse us from all unrighteousness. If we say that we have not sinned, we make Him a liar, and His Word is not in us."

1 John 3:4, "Whoever commits sin, transgresses also the Law; for sin is the transgression of the Law."

1 John 2:1-2, "My little children, I write these things to you, so that you may not sin. And if anyone sins, we have an Advocate with the Father: Yahshua Messiah, the Righteous; and He is the sacrifice of atonement for our sins, and not for ours only, but also for the sins of the whole world."

I donlt even believe that myself? Wow, you must be a real Ms. Cleo... No actually I do beleive that because of the journey I have been on learning Yah and His truth. People I met when I didn;t know the word well that knew it better than I did, seeing how hard they studied and and sought YHWH and His ways... I can look and see the change in myself, I can look and see the change in others. Doctrine aside the longer someone seeks Yah the more they should grow in His ways, this is the journey. We are all in different places..

if you think people are free to do whatever they want, why say that only those who really understand follow what you believe?

I'm not sure you know what you believe since it is a mashup of old and new testaments

you cannot please God by trying to follow parts of the law.

I'm not sure you know what you believe since it is a mashup of old and new testaments

you cannot please God by trying to follow parts of the law.

I'm not sure you know what you believe since it is a mashup of old and new testaments

Mat 4:4, “But He answering, said, “It has been written, ‘Man shall not live by bread alone, but by every word that comes from the mouth of יהוה.” (Deut 8:3)

and also He says to do and promote the Law:

Matthew 5:17-19, “Do not think that I came to destroy the Torah or the Prophets. I did not come to destroy but to fulfill. For truly, I say to you, till the heaven and the earth pass away, one yod or one tittle shall by no means pass from the Torah till all be done. Whoever, then, breaks one of the least of these commands, and teaches men so, shall be called least in the reign of the heavens; but whoever does and teaches them, he shall be called great in the reign of the heavens.”

Revelation 21:1, "I saw a new heaven and a new earth, for the first heaven and the first earth had passed away."

you cannot please God by trying to follow parts of the law.

1 John 1:8-10, "If we say that we have no sin, we deceive ourselves, and the truth is not in us. If we confess our sins, He is faithful and just to forgive us our sins, and to cleanse us from all unrighteousness. If we say that we have not sinned, we make Him a liar, and His Word is not in us."

1 John 3:4, "Whoever commits sin, transgresses also the Law; for sin is the transgression of the Law."

1 John 2:1-2, "My little children, I write these things to you, so that you may not sin. And if anyone sins, we have an Advocate with the Father: Yahshua Messiah, the Righteous; and He is the sacrifice of atonement for our sins, and not for ours only, but also for the sins of the whole world."

don't give me this everyone is on a journey nonsense when you know full well you do not even believe that yourself and you set standards for partial law obedience when the real obedience needs to come through Christ.

-

1

- Show all

Who is truth? Jesus said that HE is the Way, the TRUTH and the Life.

so follow Him...

so follow Him...

Acts 7:37-38, “This is the Mosheh who said to the children of Yisra’yl, ‘יהוה your Mighty One shall raise up for you a Prophet like me from your brothers. Him you shall hear.’ This is he who was in the assembly in the wilderness with the Messenger who spoke to him on Mount Sinai, and with our fathers, who received the living Words to give to us.”

John/Yahanan 5:46-47, "For had you believed Mosheh, you would have believed Me, for he wrote about Me*. But if you do not believe his writings, how will you believe My words?"

*Mosheh wrote:

Deuteronomy 18:18-19, “I (YHWH) will raise up for them a Prophet (Yahshua/Jesus) like you from among their brothers, and I will put My words in His mouth, and He will tell them everything I command Him. Whoever will not listen to My words, which He speaks in My Name, I will judge him for it.”

"listen" is word #8085 - שָׁמַעshama` {shaw-mah'}

Brown-Driver-Briggs (Old Testament Hebrew-English Lexicon)

A primitive root; to hear intelligently (often with implication of attention, obedience, etc.; causatively to tell, etc.)

Hebrew Word Study (Transliteration-Pronunciation Etymology & Grammar) - 1) to hear, listen to, obey

John/Yahanan 12:48, “He who rejects Me, and does not follow My words has One Who judges him. The word that I have spoken, the same will be used to judge him in the last day.”

Acts 3:19-23, “Repent therefore and turn back, for the blotting out of your sins, in order that times of refreshing might come from the presence of the Master, and that He sends יהושע Messiah, pre-appointed for you, whom heaven needs to receive until the times of restoration of all matters, of which the Mighty One spoke through the mouth of all His set-apart prophets since of old. For Mosheh truly said to the fathers, ‘יהוה your Mighty One shall raise up for you a Prophet like me from your brothers. Him you shall hear according to all matters, whatever He says to you. And it shall be that every being who does not hear that Prophet shall be utterly destroyed from among the people.”

Here are some threadsI have made in the past few months... I can go back 6 years to my original account I am locked out of not banned, and I have threads dedicated to the Messiah;s teachings and how important they are...

https://christianchat.com/bible-discussion-forum/are-the-words-of-the-messiah-above-all-else.165791/

https://christianchat.com/bible-discussion-forum/messiah-as-the-branch.166259/

https://christianchat.com/bible-discussion-forum/what-is-the-yoke-of-messiah.178880/

L

Is money a religious practice? or is that and apples to oranges comparison?

With that said people lusting for money and the power it brings can but a stumbling block. People should never put money before the Most High.

Matthew 6:19-20,19 “Do not lay up for yourselves treasures on earth, where moth and rust destroy and where thieves break in and steal,"20 but lay up for yourselves treasures in heaven, where neither moth nor rust destroys and where thieves do not break in and steal."

With that said people lusting for money and the power it brings can but a stumbling block. People should never put money before the Most High.

Matthew 6:19-20,19 “Do not lay up for yourselves treasures on earth, where moth and rust destroy and where thieves break in and steal,"20 but lay up for yourselves treasures in heaven, where neither moth nor rust destroys and where thieves do not break in and steal."

I really don't give a squat about the origin of egg dying. I consider it a fun family activity. For the record, I haven't participated in this for years but have a few happy memories as a child and later as a parent. Why take all of the joy out of life sweating the small spiritually insignificant details? There are pagan origins in just about everything we do so who really cares as long as it does not have an adverse affect on our spiritual growth. As far as traditions are concerned what are biblically wrong about them?

What is biblically wrong with them? The Most High says this:

John 4:24, “Yah is Spirit, and those who worship Him need to worship in spirit and truth.”

"Do not learn the way of the heathen" and "Be careful not to be ensnared into following them by asking about their gods, saying: How did these nations serve their gods? I also will do the same. You must not worship YHWH your Father in their way"

If indeed Christmas and Easter are pagan rituals rebranded by the Romans as "Christian" then partaking in them would directly go against the Words of Yah...

John 4:24, “Yah is Spirit, and those who worship Him need to worship in spirit and truth.”

Jeremiah 10:1-5, “Hear the word which YHWH speaks concerning you, O house of Israyl. This is what YHWH says: Do not learn the way of the heathen and do not be deceived by the signs of heaven; though the heathen are deceived by them For the religious customs of the peoples are vain; worthless! For one cuts a tree out of the forest, the work of the hands of the workman, with the ax. They decorate it with silver and with gold; they fasten it with nails and with hammers, so that it will not move; topple over. They are upright, like a palm tree, but they cannot speak; they must be carried, because they cannot go by themselves. Do not give them reverence! They cannot do evil, nor is it in them to do righteousness!”

Deuteronomy 12:29-, “When YHWH your Father cuts off the nations from in front of you, and you displace them and live in their land, Be careful not to be ensnared into following them by asking about their gods, saying: How did these nations serve their gods? I also will do the same. You must not worship YHWH your Father in their way, for every abomination to YHWH, which He hates, they have done to their gods."

L

Well to me what matters is what the Most High thinks. I grew up with Christmas and Easter personally, after learning His word I thought it good idea to follow Him only in ways He said to...

What is biblically wrong with them? The Most High says this:

John 4:24, “Yah is Spirit, and those who worship Him need to worship in spirit and truth.”

"Do not learn the way of the heathen" and "Be careful not to be ensnared into following them by asking about their gods, saying: How did these nations serve their gods? I also will do the same. You must not worship YHWH your Father in their way"

If indeed Christmas and Easter are pagan rituals rebranded by the Romans as "Christian" then partaking in them would directly go against the Words of Yah...

John 4:24, “Yah is Spirit, and those who worship Him need to worship in spirit and truth.”

Jeremiah 10:1-5, “Hear the word which YHWH speaks concerning you, O house of Israyl. This is what YHWH says: Do not learn the way of the heathen and do not be deceived by the signs of heaven; though the heathen are deceived by them For the religious customs of the peoples are vain; worthless! For one cuts a tree out of the forest, the work of the hands of the workman, with the ax. They decorate it with silver and with gold; they fasten it with nails and with hammers, so that it will not move; topple over. They are upright, like a palm tree, but they cannot speak; they must be carried, because they cannot go by themselves. Do not give them reverence! They cannot do evil, nor is it in them to do righteousness!”

Deuteronomy 12:29-, “When YHWH your Father cuts off the nations from in front of you, and you displace them and live in their land, Be careful not to be ensnared into following them by asking about their gods, saying: How did these nations serve their gods? I also will do the same. You must not worship YHWH your Father in their way, for every abomination to YHWH, which He hates, they have done to their gods."

What is biblically wrong with them? The Most High says this:

John 4:24, “Yah is Spirit, and those who worship Him need to worship in spirit and truth.”

"Do not learn the way of the heathen" and "Be careful not to be ensnared into following them by asking about their gods, saying: How did these nations serve their gods? I also will do the same. You must not worship YHWH your Father in their way"

If indeed Christmas and Easter are pagan rituals rebranded by the Romans as "Christian" then partaking in them would directly go against the Words of Yah...

John 4:24, “Yah is Spirit, and those who worship Him need to worship in spirit and truth.”

Jeremiah 10:1-5, “Hear the word which YHWH speaks concerning you, O house of Israyl. This is what YHWH says: Do not learn the way of the heathen and do not be deceived by the signs of heaven; though the heathen are deceived by them For the religious customs of the peoples are vain; worthless! For one cuts a tree out of the forest, the work of the hands of the workman, with the ax. They decorate it with silver and with gold; they fasten it with nails and with hammers, so that it will not move; topple over. They are upright, like a palm tree, but they cannot speak; they must be carried, because they cannot go by themselves. Do not give them reverence! They cannot do evil, nor is it in them to do righteousness!”

Deuteronomy 12:29-, “When YHWH your Father cuts off the nations from in front of you, and you displace them and live in their land, Be careful not to be ensnared into following them by asking about their gods, saying: How did these nations serve their gods? I also will do the same. You must not worship YHWH your Father in their way, for every abomination to YHWH, which He hates, they have done to their gods."

that's not true. you would not have source for that because it does not even exist

here is a source for FIVE different theories about why people dye eggs

note these are all theories. just because it was done in a place for whatever purpose, does not mean it is THE source for all egg dying

and here is yet more info on it:

Numerous theories exist about why dyeing Easter eggs is a popular tradition. Mental Floss and the Holiday Spot suggest various histories. While there's a strong belief dyeing eggs started as a pagan tradition, apparently the connection isn't proven. I'll share some of the ideas here.

SPRING HOLIDAYS: Easter eggs were commonly painted and dyed as a part of holiday celebrations of the new season, and this tradition (used by Persian, Egyptian and other cultures) was adopted by Christians, weaving the practice into the celebration Jesus' resurrection.

PASSOVER CONNECTION: During Passover, hard-boiled eggs dipped in salt water are used as a symbol of new life and the continued use of the symbol in the closely connected religions makes sense.

BLOOD OF CHRIST: Since early egg dyeing was often red (with an egg dye made of onion skins), there are myths stating the color represents the blood of Christ. One thought is that Mary brought boiled eggs to the crucifixion and Jesus' blood dripped on them, so the red dye highlights that occurrence.

This tradition may have also taken root in Mesopotamian culture.

JESUS' TOMB: A couple of histories connect the use of the egg with the tomb of Jesus. One being that the egg resembles the tomb rolled away from the tomb which led to the discovery of Jesus rising. Another idea involves Mary Magdalene visiting the tomb and upon discovering it empty, the bag of eggs she had with her turned red.

This list is by no means exhaustive, but some of the more popular theories about dyeing Easter eggs.

source

you cannot state something as fact when it so obviously is anything...anything...but fact.

here is a source for FIVE different theories about why people dye eggs

note these are all theories. just because it was done in a place for whatever purpose, does not mean it is THE source for all egg dying

and here is yet more info on it:

Numerous theories exist about why dyeing Easter eggs is a popular tradition. Mental Floss and the Holiday Spot suggest various histories. While there's a strong belief dyeing eggs started as a pagan tradition, apparently the connection isn't proven. I'll share some of the ideas here.

SPRING HOLIDAYS: Easter eggs were commonly painted and dyed as a part of holiday celebrations of the new season, and this tradition (used by Persian, Egyptian and other cultures) was adopted by Christians, weaving the practice into the celebration Jesus' resurrection.

PASSOVER CONNECTION: During Passover, hard-boiled eggs dipped in salt water are used as a symbol of new life and the continued use of the symbol in the closely connected religions makes sense.

BLOOD OF CHRIST: Since early egg dyeing was often red (with an egg dye made of onion skins), there are myths stating the color represents the blood of Christ. One thought is that Mary brought boiled eggs to the crucifixion and Jesus' blood dripped on them, so the red dye highlights that occurrence.

This tradition may have also taken root in Mesopotamian culture.

JESUS' TOMB: A couple of histories connect the use of the egg with the tomb of Jesus. One being that the egg resembles the tomb rolled away from the tomb which led to the discovery of Jesus rising. Another idea involves Mary Magdalene visiting the tomb and upon discovering it empty, the bag of eggs she had with her turned red.

This list is by no means exhaustive, but some of the more popular theories about dyeing Easter eggs.

source

you cannot state something as fact when it so obviously is anything...anything...but fact.

The Last Two Million Years by The Reader’s Digest Association, page 215

“Pagan rites absorbed By a stroke of tactical genius the Church, while intolerant of pagan beliefs, was able to harness the powerful emotions generated by pagan worship. Often, churches were sited where temples had stood before, and many heathen festivals were added to the Christian calendar. Easter, for instance, a time of sacrifice and rebirth in the Christian year, takes its name from the Norse goddess Eostre, in whose honor rites were held every spring. She in turn was simply a northern version of the Phoenician earth-mother Astarte, goddess of fertility. Easter eggs continue an age-old tradition in which the egg is a symbol of birth; and cakes which were eaten to mark the festivals of Astarte and Eostre were the direct ancestors of our hot-cross buns.”

Collier’s Encyclopedia, Volume 3, page 97

ASTARTE [æsta’rti], the Phoenician goddess of fertility and erotic love. The Greek name, ‘‘Astarte’’ was derived from Semitic, ‘‘Ishtar,’’ ‘‘Ashtoreth.’’ Astarte was regarded in Classical antiquity as a moon goddess, perhaps in confusion with some other Semitic deity. In accordance with the literary traditions of the Greco-Romans, Astarte was identified with Selene and Artemis, and more often with Aphrodite. Among the Canaanites, Astarte, like her peer Anath, performed a major function as goddess of fertility. Egyptian iconography, however, portrayed Astarte in her role as a warlike goddess massacring mankind, young and old. She is represented on plaques (dated 1700-1100 b.c.) as naked, in striking contrast to the modestly garbed Egyptian goddesses. Edward J. Jurji

From The Two Babylons by Hislop, pages 20-22

The Babylonians in their popular religion, supremely worshiped a Goddess Mother, and a Son, who was represented in pictures and in images as an infant or child in his mother’s arms (Figs. 5 and 6). From Babylon, this worship of the Mother and the Child spread to the ends of the earth. In Egypt, the Mother and the Child were worshiped under the names of Isis and Osiris.* In India, even to this day, as Isi and Iswara; * in asia, as Cybele and Deoius;§ in Pagan Rome, as Fortuna and Jupiter-puer, or Jupiter, the boy;11 in Greece, as Ceres, the Great Mother, with the babe at her breast,¶ or as Irene, the goddess of Peace, with the boy Plutus in her arms; ** and even in Thibet, in China, and Japan, the Jesuit missionaries were astonished to find the counterpart of Madonna ** and her child as devoutly worshiped as in Papal Rome itself; Shing Moo, the Holy Mother in China, being represented with a child in her arms, and a glory around her, exactly as if a Roman Catholic artist had been employed to set her up.* The original of that mother, so widely worshiped, there is reason to believe, was Semiramis, * already referred to, who, it is well known, was worshiped by the Babylonians, * and other eastern nations, § and that under the name of Rhea, ||the great goddess “Mother.” It was from the son, however, that she derived all her glory and her claims to deification. That son, though represented as a child in his mother’s arms, was a person of great stature and immense bodily powers, as well as most fascinating manners. In Scripture he is referred to (Ezek. viii. 14) under the name of Tammuz, but he is commonly known among classical writers under the name of Bacchus, that is, ‘‘The lamented One.’’ ¶ To the ordinary reader the name of Bacchus suggests nothing more than revelry and drunkenness, but it is now well known, that amid all the abominations that attended his orgies, their grand design was professedly ‘‘the purification of souls,’’ * and that from the guilt and defilement of sin. This lamented one, exhibited and adored as a little child in his mother’s arms, seems, in point of fact, to have been the husband of Semiramis, whose name, Ninus, by which he is commonly known in classical history, literally signified ‘‘The Son,’’* as Semiramis, the wife, was worshiped as Rhea, whose grand distinguishing character was that of the great goddess ‘‘Mother,’’* the conjunction with her of her husband, under the name of Ninus, or ‘‘The Son,’’ was sufficient to originate the peculiar worship of the ‘‘Mother and Son,’’ so extensively diffused among the nations of antiquity; and this, no doubt, is the explanation of the fact which has so much puzzled the inquirers into ancient history, that Ninus is sometimes called the husband, and sometimes the son of Semiramis.§ This also accounts for the origin of the very same confusion of relationship between Isis and Osiris, the mother and child of the Egyptians; for as Bunsen shows, Osiris was represented in Egypt as at once the son and husband of his mother; and actually bore, as one of his titles of dignity and honor, the name ‘‘Husband of the Mother.’’|| The Babylonian worship of the Great Mother spread throughout the known world. This Mother Goddess was known by different names, but the form of her religion has not transformed since antiquity...

Eggs have absolutely nothing to do with the resurrection of the Messiah (three days and three nights after He was placed in the grave),but the egg was a sacred symbol to the Babylonians. An egg of wondrous size fell from heaven into the Euphrates River; from this marvelous egg the Goddess Astarte (Easter) was hatched. From the land of Babylon, humanity was scattered to the various parts of the earth. These religious people took with them the symbol of the mystic sacred egg. Each pagan nation had its own representation of this wonder. The Greeks had their sacred egg of Heliopolis, and the Typhon’s Egg.

From The Two Babylons, by Hislop on page 109

From Egypt these sacred eggs can be distinctly traced to the banks of the Euphrates. The classic poets are full of the fable of the mystic egg of the Babylonians; and thus its tale is told by Hyginus, the Egyptian, the learned keeper of the Palatine library at Rome, in the time of Augustus, who was skilled in all the wisdom of his native country: ‘‘An egg of wondrous size is said to have fallen from heaven into the river Euphrates. The fishes rolled it to the bank, where the doves having settled upon it, hatched it, and out came Venus, who afterwards was called the Syrian Goddess’’*—that is, Astarte. Hence the egg became one of the symbols of Astarte or Easter; and accordingly, in Cyprus, one of the chosen seats of the worship of Venus, or Astarte, the egg of wondrous size was represented on a grand scale. (See Fig. 32) § The Roman Catholic Church now has their own Official Representation of Ishtar—the Virgin Mother, who stands upon the top of this Sacred Egg of Heliopolis, with the Serpent Typhon at her feet.

Continued from above.

The Interpreter’s Dictionary of The Bible, Volume 3, page 975

QUEEN OF HEAVEN - The object of worship, particularly by women, in Judah in the time of Jeremiah; cakes (konim), possibly shaped as figurines, were offered to her with libations (Jer. 7:18; 44:17-19, 25). Jeremiah censures the Jewish refugees in Egypt after the fall of Jerusalem for burning incense and offering libation to the Queen of heaven. From the second reference this cult seems to have been designed to secure material welfare. From these two isolated references, however, it is not possible to determine with certainty the object of worship, the more so because of variant readings. The MT (melekat) is an unusual form of melekah, the normal word for ‘‘queen’’ and certain MSS read melakat (‘‘handiwork’’), meaning presumably the stars; this was understood by the LXX translators in Jer. 7:18, where ‘‘the heavenly host’’ (τη στρατια του ουρανου) is read, supported by the Targ., which reads ‘‘the star(s) of heaven’’ (shemia kukbat). If ‘‘the queen of heaven’’ is to be read—which seems more probable—the reference might be to Ishtar, the goddess of love and fertility, who was identified with the Venus Star and is actually entitled ‘‘Mistress of Heaven’’ in the Amarna tablets. The difficulty is that the Venus Star was regarded in Palestine as a male deity (see day star), though the cult of the goddess Ishtar may have been introduced from Mesopotamia under Manasseh. It is possible that Astarte, or Ashtoreth, the Canaanite fertility-goddess, whose cult was well established in Palestine, had preserved more traces of her astral character as the female counterpart of Athtar than the evidence of the O.T. or the Ras Shamra Texts indicates. The title ‘‘Queen of Heaven’’ is applied in an Egyptian inscription from the Nineteenth Dynasty at Beth-shan to ‘‘antit,’’ the Canaanite fertility-goddess Anat, who is termed ‘‘Queen of Heaven and Mistress of the Gods.’’ This is the most active goddess in the Ras Shamra Texts, but in Palestine her functions seem to have been taken over largely by Ashtoreth. We have had the opportunity to read more than once throughout this booklet that the name and the festival of Easter have their origins in the worship of a pagan Goddess of spring, but Easter is now the most important of Christian festivals.

Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible:

Queen of Heaven: A goddess worshipped first in Judah in the late 7th century and then by Judahites who fled to Egypt after the Babylonian destruction of 586 b.c.e. (Jer. 7:16–20; 44:15–28). Jeremiah’s remarks associate the goddess with fertility and somewhat with war; she also, as her title indicates, has astral characteristics. The Canaanite goddess who best fits this description is Astarte, who is associated with both fertility and war and who has astral features. Phoenician inscriptions also ascribe to Astarte the title “Queen.” Astarte’s Mesopotamian counterpart, Ishtar, whose female devotees ritually weep in imitation of the goddess’ lamentations over her dead lover, Tammuz (Ezek.8:14).

same religious practice all over the world, Ashtoreh, Ishtar, Easter, Eostre, etc.

The Interpreter’s Dictionary of The Bible, Volume 3, page 975

QUEEN OF HEAVEN - The object of worship, particularly by women, in Judah in the time of Jeremiah; cakes (konim), possibly shaped as figurines, were offered to her with libations (Jer. 7:18; 44:17-19, 25). Jeremiah censures the Jewish refugees in Egypt after the fall of Jerusalem for burning incense and offering libation to the Queen of heaven. From the second reference this cult seems to have been designed to secure material welfare. From these two isolated references, however, it is not possible to determine with certainty the object of worship, the more so because of variant readings. The MT (melekat) is an unusual form of melekah, the normal word for ‘‘queen’’ and certain MSS read melakat (‘‘handiwork’’), meaning presumably the stars; this was understood by the LXX translators in Jer. 7:18, where ‘‘the heavenly host’’ (τη στρατια του ουρανου) is read, supported by the Targ., which reads ‘‘the star(s) of heaven’’ (shemia kukbat). If ‘‘the queen of heaven’’ is to be read—which seems more probable—the reference might be to Ishtar, the goddess of love and fertility, who was identified with the Venus Star and is actually entitled ‘‘Mistress of Heaven’’ in the Amarna tablets. The difficulty is that the Venus Star was regarded in Palestine as a male deity (see day star), though the cult of the goddess Ishtar may have been introduced from Mesopotamia under Manasseh. It is possible that Astarte, or Ashtoreth, the Canaanite fertility-goddess, whose cult was well established in Palestine, had preserved more traces of her astral character as the female counterpart of Athtar than the evidence of the O.T. or the Ras Shamra Texts indicates. The title ‘‘Queen of Heaven’’ is applied in an Egyptian inscription from the Nineteenth Dynasty at Beth-shan to ‘‘antit,’’ the Canaanite fertility-goddess Anat, who is termed ‘‘Queen of Heaven and Mistress of the Gods.’’ This is the most active goddess in the Ras Shamra Texts, but in Palestine her functions seem to have been taken over largely by Ashtoreth. We have had the opportunity to read more than once throughout this booklet that the name and the festival of Easter have their origins in the worship of a pagan Goddess of spring, but Easter is now the most important of Christian festivals.

Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible:

Queen of Heaven: A goddess worshipped first in Judah in the late 7th century and then by Judahites who fled to Egypt after the Babylonian destruction of 586 b.c.e. (Jer. 7:16–20; 44:15–28). Jeremiah’s remarks associate the goddess with fertility and somewhat with war; she also, as her title indicates, has astral characteristics. The Canaanite goddess who best fits this description is Astarte, who is associated with both fertility and war and who has astral features. Phoenician inscriptions also ascribe to Astarte the title “Queen.” Astarte’s Mesopotamian counterpart, Ishtar, whose female devotees ritually weep in imitation of the goddess’ lamentations over her dead lover, Tammuz (Ezek.8:14).

same religious practice all over the world, Ashtoreh, Ishtar, Easter, Eostre, etc.

Making others feel loved and cared about like giving someone a gift like a warm coat for winter seems to me can be of spirit n truth.

that is a big stretch you ar making trying to connect charity and pagan traditions are not needed to do that. Especially pagan traditions painted over/in the name of the Messiah.

L

I agree, and that has zero to do with a tree, a man in a red suit who know everything you do, the winter solstice, wreath, galrand, etc.

that is a big stretch you ar making trying to connect charity and pagan traditions are not needed to do that. Especially pagan traditions painted over/in the name of the Messiah.

that is a big stretch you ar making trying to connect charity and pagan traditions are not needed to do that. Especially pagan traditions painted over/in the name of the Messiah.

Correct and if people give and help others during Christmas it's ok, would it be nice to have Christmas everyday in which everyone is giving and recieving help,support, compassion. why would anyone disagree with giving and receiving.

and yes people do help around christmas time but way way way way more people are focusing on pure consumerisim, going in debt, all children learn is materialsim, what "am I getting for Christmans" It is the minority, the vast minority that is not indulging in the materialisim. You are really stretching to try and justify pagainisim, pagan rituals are not needed to perform charity.

Well to me what matters is what the Most High thinks. I grew up with Christmas and Easter personally, after learning His word I thought it good idea to follow Him only in ways He said to...

What is biblically wrong with them? The Most High says this:

John 4:24, “Yah is Spirit, and those who worship Him need to worship in spirit and truth.”

"Do not learn the way of the heathen" and "Be careful not to be ensnared into following them by asking about their gods, saying: How did these nations serve their gods? I also will do the same. You must not worship YHWH your Father in their way"

If indeed Christmas and Easter are pagan rituals rebranded by the Romans as "Christian" then partaking in them would directly go against the Words of Yah...

John 4:24, “Yah is Spirit, and those who worship Him need to worship in spirit and truth.”

Jeremiah 10:1-5, “Hear the word which YHWH speaks concerning you, O house of Israyl. This is what YHWH says: Do not learn the way of the heathen and do not be deceived by the signs of heaven; though the heathen are deceived by them For the religious customs of the peoples are vain; worthless! For one cuts a tree out of the forest, the work of the hands of the workman, with the ax. They decorate it with silver and with gold; they fasten it with nails and with hammers, so that it will not move; topple over. They are upright, like a palm tree, but they cannot speak; they must be carried, because they cannot go by themselves. Do not give them reverence! They cannot do evil, nor is it in them to do righteousness!”

Deuteronomy 12:29-, “When YHWH your Father cuts off the nations from in front of you, and you displace them and live in their land, Be careful not to be ensnared into following them by asking about their gods, saying: How did these nations serve their gods? I also will do the same. You must not worship YHWH your Father in their way, for every abomination to YHWH, which He hates, they have done to their gods."

What is biblically wrong with them? The Most High says this:

John 4:24, “Yah is Spirit, and those who worship Him need to worship in spirit and truth.”

"Do not learn the way of the heathen" and "Be careful not to be ensnared into following them by asking about their gods, saying: How did these nations serve their gods? I also will do the same. You must not worship YHWH your Father in their way"

If indeed Christmas and Easter are pagan rituals rebranded by the Romans as "Christian" then partaking in them would directly go against the Words of Yah...

John 4:24, “Yah is Spirit, and those who worship Him need to worship in spirit and truth.”

Jeremiah 10:1-5, “Hear the word which YHWH speaks concerning you, O house of Israyl. This is what YHWH says: Do not learn the way of the heathen and do not be deceived by the signs of heaven; though the heathen are deceived by them For the religious customs of the peoples are vain; worthless! For one cuts a tree out of the forest, the work of the hands of the workman, with the ax. They decorate it with silver and with gold; they fasten it with nails and with hammers, so that it will not move; topple over. They are upright, like a palm tree, but they cannot speak; they must be carried, because they cannot go by themselves. Do not give them reverence! They cannot do evil, nor is it in them to do righteousness!”

Deuteronomy 12:29-, “When YHWH your Father cuts off the nations from in front of you, and you displace them and live in their land, Be careful not to be ensnared into following them by asking about their gods, saying: How did these nations serve their gods? I also will do the same. You must not worship YHWH your Father in their way, for every abomination to YHWH, which He hates, they have done to their gods."

L

truth or tradition, each one will choose.

I see your heart.

I see your heart.

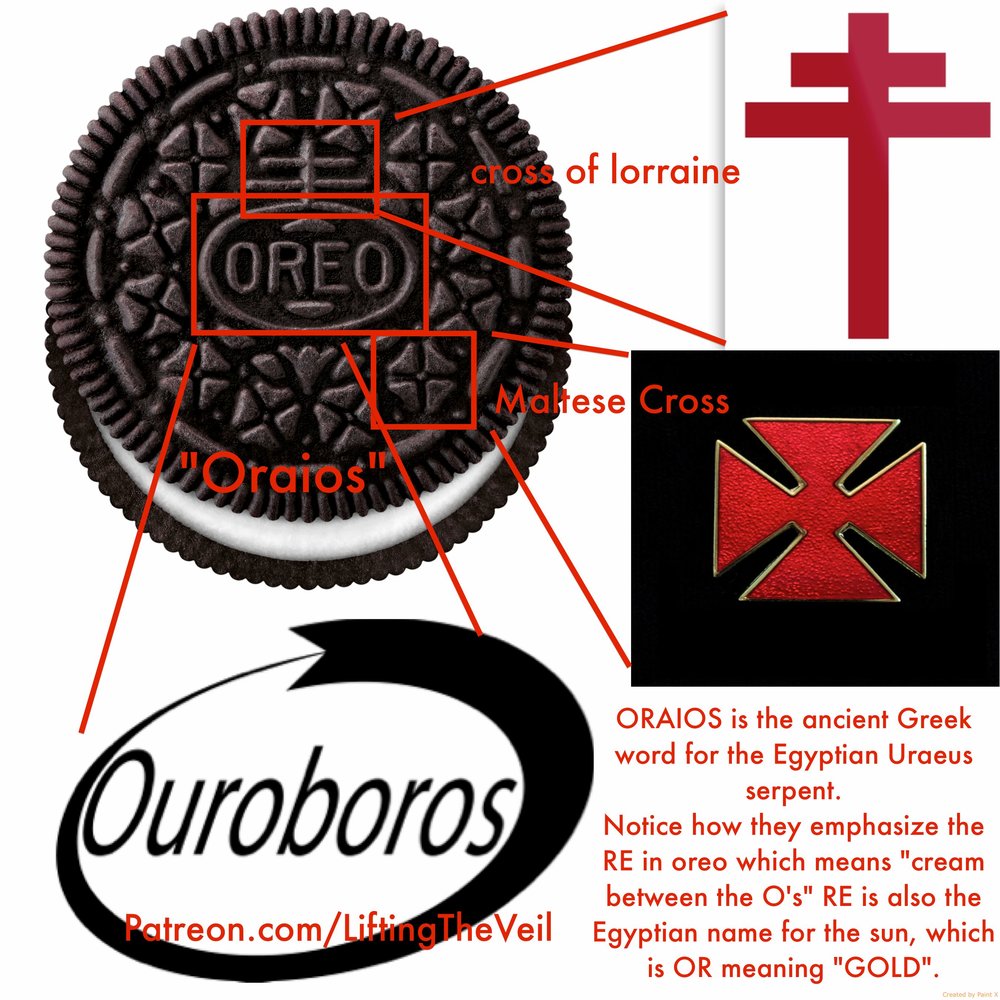

Many things have pagan roots the names of days most the world uses and a whole laundry list of things. the cross the crucifix has pagan roots. the pagans first started the hanging on the cross/cruxifix as a religionous practiced if a person did bad things sinned while living etc, dying it was a honor to them to be crucified hung above the ground as to not spoiled the ground and leave bad vibes whatever, well the Romans knew of that practiced and turned it into a punishment. thus how they started crucifying.

-

2

- Show all